By Claire Ballentine and Alice Kantor

In the Before Times, people had to make a choice: Squeeze into the chaos and energy of the city, or live large amidst the beauty and boredom of the countryside.

The pandemic led many to reevaluate this lifestyle choice, upending global housing markets. Prices skyrocketed and bidding wars abounded in the suburbs, while demand plummeted in many big cities. Now, those who can afford it want both.

In New York, one family is dividing their time between their Greenwich Village apartment and upstate home. About 800 miles west, a financial analyst is bouncing between his parents’ beach house on Lake Michigan in Long Beach, Indiana, and his boyfriend’s apartment in Chicago.

On the other side of the Atlantic, a real estate analyst is chasing a better work-life balance with his wife and kids by spending more days in their countryside home outside of Paris. A small business owner in Rome is renting out her apartment next to the Colosseum while spending time in her new house 40 minutes away in the Sabine Hills. One London apartment owner is saving money by splitting his time between the capital and the Cotswolds, in the rolling hills of south-central England.

“Hybrid living is the catchphrase of the day,” said Leonard Steinberg, chief evangelist of real estate brokerage Compass Inc. “The perception is that if you have a second home, you have to be a billionaire, but what we’ve recognized especially in the past 18 months is that it’s possible to have a small apartment in the city and a small home outside the city.”

Low interest rates on home loans, pandemic-era savings and a hybrid-work revolution have made it more feasible for people, not just the ultra rich, to live a dual lifestyle. That fundamental change in where and how people live stands to infuse second-home markets, once reliant on weekenders and seasonal visitors, with greater demand for restaurants, retail and other amenities that make urban dwelling so appealing.

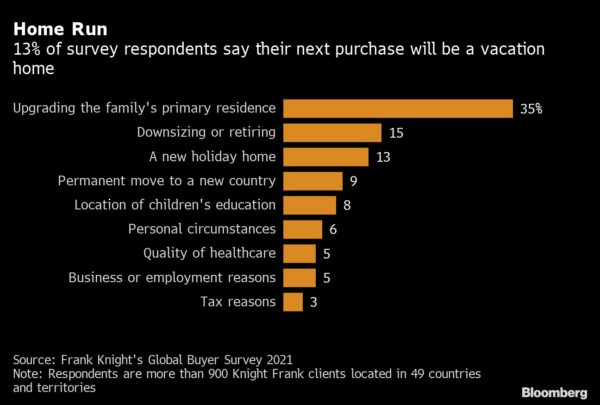

Already, about 19 percent of respondents in Knight Frank’s 2021 Global Buyer Survey said they moved since the start of the pandemic. And there may be more to come: 33 percent of respondents said they were more likely to buy a second home as a result of the pandemic, up from 26 percent the prior year.

“With the rise of remote working, second homes or ‘co-primaries’ are becoming a viable option for more buyers seeking a better work/life balance,” the report said.

Read More: The Hybrid Work Revolution Is Already Transforming Economies

For the people who can pull off hybrid living, it’s a financial and physical feat. But mental health professionals say the supposed luxury of double living may be a stressor in the long term. Having to juggle multiple rents or mortgages and frequently schlepping from place to place can be daunting.

“There’s the pressure you need to go there,” said Sharon Saline, a licensed clinical psychologist in Northampton, Massachusetts. “You’ve spent this part of your income or savings on the second home — you want to make sure you use it or get your money’s worth.”

Two of Everything

For Keri Cibelli, an environmental consultant in New York City, it wasn’t until the pandemic that she and her family began spending substantial time at their vacation home in Dutchess County, a trendy enclave along the Hudson River in upstate New York.

In March 2020, the family packed up and headed north, enrolling their kids in a local private school and extracurricular activities. But now Cibelli’s sons are back in school in the city, she goes into her office twice a week and her husband goes in every day, so the family is spending weekdays in their West Village apartment and returning upstate each weekend.

“It feels like we have two communities now,” she said. “The city first and foremost is where our jobs are, and we wanted to raise our kids in the city. The shift is just having both and exposing our kids to both.”

The boys are still enrolled in weekend sports leagues and piano lessons that they started in Dutchess County during the pandemic. And the family uses the two-hour drive back to the city on Sunday evenings to plan for the week ahead and catch up on podcasts like NPR’s “Wait Wait… Don’t Tell Me.”

Fortunately, the family’s pandemic escape was already in the budget. Cibelli and her husband purchased the three-bed, two-bath Dutchess County home for $475,000 five years ago — so they were already juggling two mortgages, $300 for trash and utilities upstate, a $500 car payment and a $500 monthly fee at the parking garage in the city. The only added costs have been gas for all the extra driving, supplies to keep both homes stocked and a $175 price increase from the garage as demand skyrocketed.

“It’s a transition trying to manage both, but we’re doing it,” she said. “I do question it, but it’s worth it.”

Cibelli said she has “two of everything” for her kids and herself — clothes, toiletries. She’s even split up medication bottles.

That’s a key way to reduce stress tied to shuttling between two places, according to Frances Walfish, a family psychotherapist in private practice in Beverly Hills, California.

“One of the best ways to reduce anxiety about shifting and adjusting to and from the homes is to stock both homes with as much of the supplies you need — custodial supplies, toothpaste, toothbrush, clothing, shoes,” she said. “It’s easy to pick up your car keys, jump in the car and go.”

Best of Both

Hybrid living has led to cost-savings for some.

Amy Lentini, an American small business owner, was living full-time in an apartment next to the Colosseum in Rome before she decided to buy a house in the Sabine Hills. Initially envisaged as a summer spot to avoid the city heat, the house became a primary residence for her and her partner during the pandemic.

The 220-square-meter home required a lot of money and time at first: Lentini said she had to do renovations, buy furniture, deep clean, hire someone to maintain the 2-acre garden, and pay for a car and insurance.

So when an acquaintance inquired about renting out her Roman apartment every other month, “it was quite unexpected and a happy coincidence,” Lentini said. “If it wasn’t for the extra rent money, we would have to be much more aware of our spending.”

Now, Lentini is more committed to her home in the Sabine Hills.

“We don’t feel like urban dwellers anymore… It feels like we’re on vacation when we come back to Rome,” she said. “I see exhibitions, go to museums, go to lunch with my daughter, then I head back to the Sabine Hills for olive season.”

For 41 year-old Romain Picard, splitting his time between his Paris apartment and his house in the hinterland has given him more of a work-life balance. In addition to spending weekends at a cottage in Blévy in the Loire Valley with his wife and two kids, the senior tech manager will spend some weekdays working remotely. He finds he has better concentration, less stress and is overall more productive.

“Yes, we pay more for gas, but we’re comfortable financially and in the long term we know that this will have a positive impact on our health and mental well-being,” he said.

In the U.K., Knight Frank real estate agent Jonathan Bramwell found that by splitting time between his apartment in London and his girlfriend’s home in the Cotswolds, he’s spending less money now than when he was in the city everyday.

“Suddenly I’m not going to Pret twice a day,” he said, referring to the popular U.K. sandwich chain. But as more people are spending time in the countryside, those restaurants and bars are starting to charge London prices, he said.

The same principle applies to real estate. A 2020 study published in the Journal of the Geographical Institute Jovan Cvijic found that owners of second homes can contribute to increases in home prices and the overall cost of living in their communities. But there are also economic benefits like new jobs and more shopping options and recreational facilities.

“You have the best of both worlds,” said London-based Hamptons real estate agent William Neville Smith, who has observed a rise in the number of pieds-à-terre purchased in London. “There’s been a lot of talk of people buying in the countryside to get more space, but no one’s highlighted the fact that a lot of people also enjoy the buzz of living in a big city like London.”

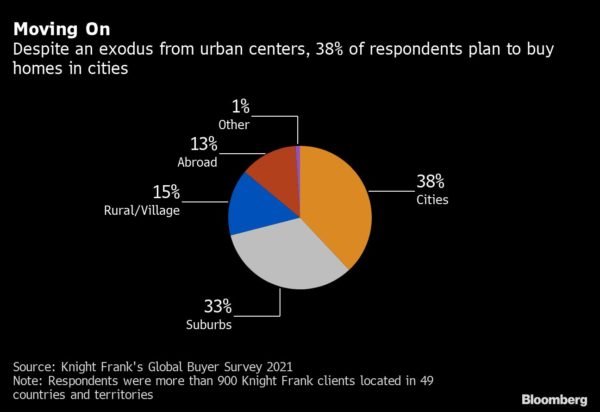

Demand for apartments has increased globally in 2021, according to Knight Frank, as people look for larger places and pieds-à-terre to use as mid-week bases: 19 percent of survey respondents said they wanted to buy apartments this year, up from 12 percent last year. And of those looking to move within the next year, the most at 38 percent are looking at cities.

Reverse Commute

That’s the case for Megan Chan Meinero and Jodie Tassello, who recently took on a third home — this one in Manhattan.

During the pandemic, the couple lived primarily in a rented 1,000-square-foot cottage on the Hudson River in Nyack, New York, while spending their weekends in a Catskills home they bought in 2018. As the New York theater district began reopening, Meinero — a screenwriter and playwright — felt the city luring her in. Although they didn’t score a Covid deal, they couldn’t pass up the location.

“I had never lived in Manhattan, and I really wanted to,” she said. “It was kind of an impulsive move, but we found this apartment and we fell in love with it. I love that I can walk to a Broadway theater in 15 minutes.”

They’re far from alone. About 25 percent — or 874 — of new listings for sale in Manhattan in the second quarter of 2021 were billed as “pied-à-terre friendly,” a figure that’s stayed roughly consistent before and throughout the pandemic, according to data from real estate analytics firm UrbanDigs.

The couple’s one-bedroom, one-bathroom apartment in Hell’s Kitchen on 52th Street now serves as their primary home, with Tassello commuting to Rockland County near their Nyack home during the week to run her acupuncture practice. They usually spend weekends in Nyack, and longer breaks or vacations in the Catskills — though they change it up based on how they’re feeling.

They declined to say how much they’re spending on the three places — two rents and one mortgage — but said that each of the three is under $5,000. “The city is the smallest and the most expensive, and the upstate house is the largest and the cheapest,” Meinero said.

They’ve invested in three of everything, from hairdryers to their dog’s medication, so they only carry a backpack with some clothes when they travel between homes. The couple acknowledged that having three homes sounds crazy and juggling the logistics can be tricky, but they enjoy having options.

“We kind of just go with things and figure them out,” Tassello said. “We just make the decisions that make us feel happy, and if something isn’t working out, we change lanes and go in a different direction.”

Social Stressors

Financial analyst Sean Mulroy stayed in his parents’ beach house on Lake Michigan in Long Beach, Indiana during the pandemic and now splits his time between the vacation home and Chicago, where his boyfriend lives and his office is located.

“I’m able to sit on the beach and enjoy my weekends there, but I have my life in the city I don’t want to give up,” he said. Plus “my job is not going to be moving to Indiana,” Mulroy said. He typically goes into the office two or three days a week.

Mulroy previously had a one-bedroom condo in Chicago’s West Loop that was less than 1,000 square feet. He ended up selling it in May after realizing just how small it was. He bought a 2,000-square-foot apartment in the nearby Ukrainian Village but is waiting to move in. In the meantime, he stays at his boyfriend’s, but recognizes the inconveniences of double living.

“I live basically out of the trunk of my car,” he said. “It’s a bit embarrassing. Every time, I leave one house, I leave with a carry-on bag.”

He finds he has to pay extra on transportation compared to his previous lifestyle. Parking in the city is about $30 a day, along with the cost of gas. Plus, there’s the mental toll of having to plan out where he’s going to be when and what he needs to pack.

Perhaps the most significant strain is on his friendships.

“The biggest unintended consequence of the whole thing is that my friendships in the city feel more distant than they ever had,” he said. “I feel like I’m almost bullying people to come out and visit me in Indiana.”

It’s an understandable stressor.

“You get into your routine in place A, you know where things are, then suddenly you’re taken out of that routine,” said Saline, the psychologist. “You have to adjust. Given the amount of stress so many kids and adults have been under with Covid, there are changes people are making everyday. To add more changes to that could be overwhelming or not worth it.”

For some, having both is a win-win.

“When I’m in the city, I’m missing upstate and when I’m upstate, I’m missing the city,” said Cibelli. “I’m just so happy to have both.”

More stories like this are available on bloomberg.com.