By Claire Ballentine

Most everywhere you look on Wall Street, interest rates are going up. For everyday savers: not so much.

The two-year U.S. Treasury yield had its biggest one-day jump in more than a decade last week, reaching as high as 1.64%, a level unseen since late 2019 and up from 0.44% at the end of November. The U.S. 10-year yield — a global borrowing benchmark — topped 2% for the first time since August 2019.

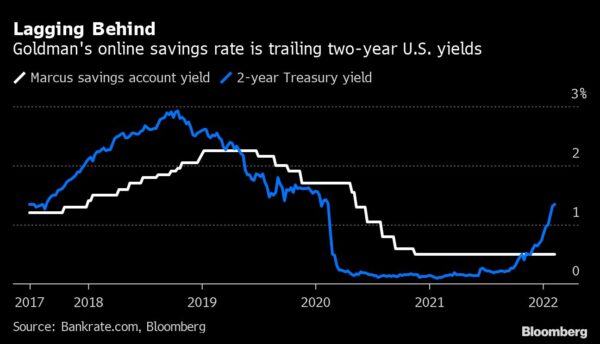

In mid-2019, Goldman Sachs Group Inc.’s popular consumer bank Marcus was also offering individuals a yield in excess of 2% to park their cash in a high-yield savings account. At the start of 2020, at which point the Federal Reserve had lowered interest rates three times, it was still promoting a 2% rate on an 11-month, no-penalty certificate of deposit.

The rates are much lower today, even though U.S. yields are back at pre-pandemic levels. Marcus’s savings rate is 0.5%, which it notes on its website is higher than Bank of America Corp.’s 0.04% or JPMorgan Chase & Co.’s 0.02%. While Goldman is in line with other high-yielding peers, like Barclays Plc and Ally Bank, rarely has its average percentage yield fallen so far behind the going rates in the $22.9 trillion U.S. Treasury market.

Online high-yield savings accounts gained popularity in recent years as a straightforward way for regular investors to keep their cash reserves liquid while still generating a return superior to accounts at the biggest U.S. retail banks. Throughout most of the pandemic recovery, ultra-safe options like these have trailed the gains on broad stock-market indexes and other risky assets.

But with the S&P 500 Index down 7.7% so far this year and the tech-heavy Nasdaq 100 losing almost 13%, people may be seeking out ways to protect their money from further losses — especially if the risk-free rates they could earn are on the way up.

However, even with bond traders quickly pushing interest rates higher, experts warn that it’ll be a slower process at banks, even those who have promised their customers “high yields.”

Banks simply aren’t as desperate as they once were for new deposits, said Kevin Caron, portfolio manager for Washington Crossing. Pandemic-era fiscal stimulus pumped so much cash into the financial system that, combined with post-2008 banking regulations, it strained the balance sheets of some of the largest U.S. lenders. Last year, JPMorgan Chief Executive Officer Jamie Dimon said there was a risk it would have to turn away deposits.

That gives institutions like Marcus and other online banks the leverage to keep their interest rates pinned where they are, at least until the Fed actually raises its key short-term benchmark.

“When the Fed does raise short rates, it’s going to put pressure on banks to increase the rates,” Caron said. “But the banks have plenty of deposits, so you might find some lag.”

Plus, banks are playing “a game of chicken” where they’re trying to keep their rates low as long as they can to avoid paying out more in interest, said Mike Bailey, director of research at FBB Capital Partners.

“After the first bank breaks from the pack and raises rates, it’s game on and you get other banks getting on the bandwagon to make sure they don’t lose market share,” he said.

When the Fed raised interest rates in 2017 and 2018, the online bank accounts gradually began offering higher yields, and then slowly cut them as the central bank eased policy.

In the Fed’s previous tightening cycle, however, inflation was barely above its 2% target, allowing central bankers to gradually boost rates by roughly 25 basis points each quarter. That kind of predictability is hardly a given this time around: The consumer price index increased by 7.5% in January from a year earlier, the fastest pace since 1982. In the wake of that data, St. Louis Fed President James Bullard said he could see the central bank needing to boost interest rates by 100 basis points in the first half of 2022 to quell inflationary pressures.

To be sure, other Fed officials have expressed a more sanguine attitude. And there’s still doubt among investors that the central bank, which has long been viewed as working to support financial markets, will show such urgency to tighten monetary policy. That could be another reason that online banks have been slower to react to swings in rates markets.

“While rates are likely to go up this year, it might be slower moving than what the Fed and the market are projecting,” said Matt Miskin, co-chief investment strategist at John Hancock Investment Management. “It’s still going to be a tougher income environment for savers.”

For everyday investors who want to capitalize on higher U.S. yields, the options aren’t as simple as a savings account. Some online brokerages offer a way to buy Treasury securities through the secondary market, while the government has its own electronic marketplace, TreasuryDirect. Exchange-traded bond funds, a popular choice among retail investors, can decline in value.

Especially when it comes to locking money into a product, timing is everything. But overthinking — or choosing to do nothing with your savings — can be even worse, given that cash is losing its purchasing power after adjusting for above-7% inflation.

“It goes back to a balanced portfolio and having cash there for shorter-term needs and maximizing all of it,” Miskin said. “You really have to be thoughtful in the financial planning element and invested for that capital that has a longer time horizon.”

More stories like this are available on bloomberg.com.