By Matthew Boyle

American workers are losing faith in their organizations’ responses to racial injustice, and some are willing to leave their job over it.

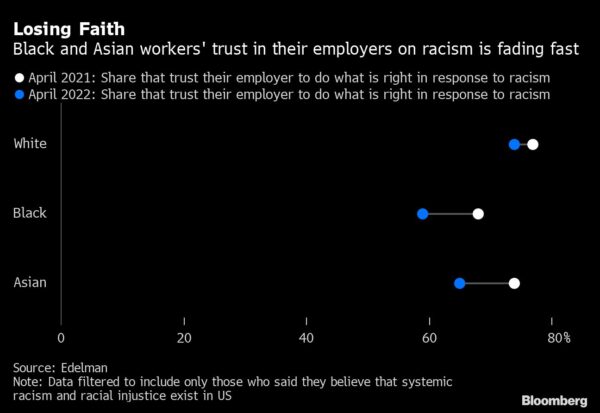

Trust in employers to “do what is right” regarding racism has declined over the past year, particularly among Black and Asian workers who believe racism exists, according to new data from communications firm Edelman. Notably, the person with the least credibility when it comes to talking about racism inside an organization is the head of diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI).

“It’s window dressing,” said Edelman’s U.S. Chief Executive Officer Lisa Osborne Ross, referring to organizations’ tendency to install a senior-level person of color to head DEI efforts without considering their qualifications or giving them a “license to drive change.” The average chief diversity officer lasts less than two years in the role, according to executive recruiter Russell Reynolds Associates, and 60% of those who had such titles in 2018 have left — the majority for other fields.

“There’s a feeling that there’s this one person who can come in and save the company,” said Deepa Purushothaman, an author and co-founder of nFormation, a research and advocacy group for women of color. “It doesn’t work that way.”

High-Profile Pledges

The declining trust on matters of race comes more than two years after companies like Walmart Inc. and Bank of America Corp. made headline-grabbing pledges and multimillion dollar investments to address racial inequities in the wake of George Floyd’s murder. Those “big lofty statements” raised hopes that companies could make great strides on combating systemic racism, Ross said, but “there’s a gap between the expectations that were raised and the delivery. It didn’t happen.”

Diversity advocates have also suffered setbacks recently, like a California judge’s decision last month to scrap a mandate requiring corporate boards of directors to include minorities.

The pandemic has prompted white-collar and so-called frontline workers to reassess their careers, sending quit rates to record highs. Remote work has appealed to many under-represented minorities, according to researchers, as it can shield them from the verbal and nonverbal slights they often face in office environments.

Now, with communities of color on edge following racially-motivated shootings in recent years, a company’s inability to address inequities could lead it to lose ground in the war for talent. Six out of ten workers said they wouldn’t take a job, or have left a job in the last year, because the employer failed to address racism within the organization or speak out against racial injustice, Edelman found. That’s a slight uptick from last year. Among younger Americans, the figure was nearly three out of four.

“Employees now require this in the workplace,” Ross said. “And if they don’t get it, they will go someplace else.”

‘Set the Tone’

While diversity chiefs garnered the least credibility from the employees surveyed, Ross said the responsibility for that lies squarely with CEOs who often sideline DEI efforts or don’t include the head of DEI among their direct reports.

“The CEO must set the tone,” she said. Yet fewer than half of senior DEI leaders strongly agree that their CEO views their position as a must-have role, according to a separate survey from PR agency Weber Shandwick.

Despite the dip in faith, workers still trust their employers’ response to racial injustice more than those of government, the media or non-government organizations (NGOs), Edelman found.

“Business is by default the most important entity here, but you can’t fix what was born in this country hundreds of years ago in two years,” Ross said. “It’s so much more complicated, so much more rooted.”

More stories like this are available on bloomberg.com.