By Sarah Rappaport

After chalking up major financial victories for the families of George Floyd and other victims of police brutality, civil rights lawyer Ben Crump said he’s eyeing the U.S. banking system as his next target.

In an interview ahead of the June 19 release of Civil, a Netflix documentary about him, Crump said he also plans to continue his efforts to use the civil courts to achieve racial justice. Money talks, as he put it: Big payouts from local governments and corporations can make a difference in how Black people are treated.

In April, Crump, a personal-injury lawyer, joined a lawsuit against Wells Fargo & Co. over racial disparities in home-lending practices. He has called on governments and other institutions to stop doing business with the bank. Bloomberg in March published an article showing that Wells Fargo approved just 47% of Black homeowners who completed applications to refinance mortgages in 2020, compared with 72% of White applicants.

The pharmaceutical industry and the case of Henrietta Lacks, the Black woman whose “immortal” cells underpin many modern-day biomedical breakthroughs, are also in his sights. He awaits a Baltimore federal district judge’s ruling on whether to dismiss a lawsuit he filed against one biomedical company, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., on behalf of the Lacks family.

Crump, 52, is one of the US’s most prominent civil rights lawyers. He led the legal team that negotiated a $27 million settlement with the city of Minneapolis for the family of George Floyd — the largest pretrial settlement in a civil rights wrongful-death case. He also represented the families of Ahmaud Arbery, the jogger whose killers were sentenced in January to life in prison; Breonna Taylor, killed in 2020 by police during a botched drug raid; and Trayvon Martin, the teen shot dead by a neighborhood watchman in 2012.

Crump has been referred to as “Black America’s attorney general” by Al Sharpton, the minister-turned-activist and TV commentator. Fox News has called him “the most dangerous man in America.”

The documentary, timed for release on Juneteenth, follows him around the country in 2020 and 2021 as the Black Lives Matter movement gained international prominence and sparked outrage about the treatment of Black people by the police.

Crump is seen meeting grieving family members, preparing for jury trials and speaking to the press about his cases. It seems the subtext is to counter how some critics have portrayed him — as a media savvy, ambulance-chasing, contingency-fee lawyer — by showcasing his journey from humble roots in rural North Carolina to becoming a lawyer and meeting his hero, Supreme Court Associate Justice Thurgood Marshall. Interspersed throughout are intimate moments between Crump and his wife and daughter.

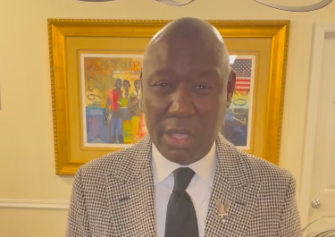

Wearing a pinstriped suit, green tie and his trademark Eagle of Justice pin, he spoke to Bloomberg via Zoom. He was joined by Nadia Hallgren, the Emmy-nominated director (Becoming: Michelle Obama) of the documentary.

Who is the intended audience for the film?

Hallgren: We are trying to reach the widest audience possible for this movie and that’s why Netflix is such a great platform for us to showcase Ben’s story. This film is for everyone. For a Black audience, we get to see our stories on screen in a nuanced and thoughtful way and that doesn’t happen enough. It’s also an opportunity for us to process this traumatic experience that reached its heights in America during the time I was filming with Ben. We’re also looking to reach an international audience to help people understand the Black experience in America beyond the news cycle.

Crump: One of the reasons I agreed to do this and pull back the curtain and to share my life is because we’re trying to influence the hearts and minds of people to make a better world for our children. Netflix has this global bullhorn that we can use to speak truth to power at a global level. And it’s one of those opportunities to try to say to the world, when you look at George Floyd, when you look at Ahmaud Arbery, we’re better than this, America can be better than this. We have to choose love over this race-replacement, lynch-mob mentality. We have to choose humanity over White supremacy. I think that’s what we talk about in Civil.

Ben, you say you want to make it financially prohibitive to murder Black people—can you expand on that?

We cannot control the criminal justice system. It seems when police kill marginalized people of color, especially Black and Brown people, nothing ever happens to them. But what we can do is employ the civil system. We’re trying to raise the value of Black life in America, so it will become financially unsustainable for the police to keep killing Black people unjustly. They can show such restraint in White people, but no such considerations for Black people.

As we saw in the Jan. 6 riots? You mention that in the film.

That’s the perfect example of that, we saw them show restraint. But with a Black person, it’s shoot first and ask questions later. And our children are dying so we have to do everything we can to stop it.

We are two years on since George Floyd was murdered—what’s changed?

Hallgren: We started making this film after that, so it’s a question we asked ourselves. Everything that we filmed was post-George Floyd’s murder. We see the killing of Daunte Wright, we see the killing of Fred Cox, of Andre Hill in the film. People were quick to rush and say things have changed, and that people took to the streets. My personal experience is that not a whole lot has changed since then in terms of excessive-force murders by police.

Crump: I’m a little more optimistic because I see how much the consciousness level in America and the world has been raised since George Floyd. Before they thought we were exaggerating, but when you watch that documentary of Floyd being tortured to death, you see the truth. I think we are making incremental, but significant progress. The fact that we had President Biden sign the executive order on policing was progress. We had 150 cities and municipalities pass laws to say we’re not going to allow police to use the chokehold. It was legal in most cities before and they were only using it against Black and Brown people. One thing that I learned was that after the civil rights act was signed, there was a study and there was almost no progress the next year in who was voting. But 10 years on, there were Black mayors and congressmen. Things had changed after time. That gives me hope.

Hallgren: Ben is more optimistic than me.

What other reforms are needed? The Senate didn’t pass the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act, for example.

Crump: We need to make the United States Senate pick people over politics, and that’s still a struggle. Many states and municipalities need to create guidelines and act. The Executive Order by President Biden creates a national database, so we don’t have to use newspapers to see how many people were killed by police, or what race they were. This is important. People will live and die, but the institutions of law will remain.

What’s next for you, Ben?

We’re still working on the environmental racism case. We’re also looking at Wells Fargo and banking while Black. A lot of Black families were denied refinancing or home loans that could have closed the wealth gap between White and Black citizens. And that’s so fundamentally important in raising the value of Black lives to be equal to White lives. You have to understand that our world is a capitalistic society, so we have to close this gap. And we’re also dealing with medical racism, with Henrietta Lacks. Her immortal cells have been used for every medical innovation in the last 70 years. But her family haven’t made one penny and the pharmaceutical companies made billions. We think that’s going to be a real landmark case. Because at the end of the day, Black lives aren’t irrelevant. We matter. And we want the world to see that.