By Maria Paula Mijares Torres and Jonnelle Marte

A Las Vegas bartender coping with a recent cancer diagnosis is fearing eviction. A young professional in Tucson is skipping car payments to afford her higher rent. A researcher in Miami signed the lease for her new apartment sight unseen.

Rental costs in the US are soaring at the fastest pace in more than three decades, surpassing a median of $2,000 a month for the first time ever and pushing rents above pre-pandemic levels in most major cities. Increases are particularly steep in metropolitan areas that saw large influxes of new residents during the pandemic, but the rental market is sparing almost nowhere and no one.

While the affordability crisis in the US is not new, it has snowballed over the past year as people returned to big cities and some areas short on housing supply saw a boom of new residents. Demand for rentals has soared, with many would-be homebuyers backing out of the market after mortgage rates jumped this year as a result of the Federal Reserve’s aggressive interest-rate hikes.

Tight inventory is leading to bidding wars, typically more a fixture of the homebuying market. Rising costs and a shortage of available units are giving landlords the leverage to hike rents at all price points. And the end of the federal eviction moratorium, combined with dwindling rental assistance, has forced people to make tough choices.

“It’s pretty much the perfect storm for renters right now,” said Kate Reynolds, principal policy associate at the Washington-based Urban Institute. “Those renters and their landlords don’t have a place to turn if they’re unable to pay the rent.”

Inflation Pressure

Many renters, who typically spend a greater share of their income on housing than homeowners, are already struggling to keep up with larger bills at the grocery store and the gas station thanks to inflation running near the highest in four decades. And rent hikes are expected to persistently push inflation higher, since leases are staggered and renters face shocks at different times. Shelter costs account for about a third of the closely watched consumer price index, which increased by 8.5% in July from a year earlier, according to Labor Department data released Wednesday.

People of color and those with lower incomes are the most affected by the increase in rent prices, since they account for the majority of renters. In the US, about 58% of households headed by Black adults rent their homes, along with nearly 52% of Latino-led households, according to a Pew Research Center analysis of census data. In comparison, about a quarter of households led by non-Hispanic White adults, and a little under 40% of Asian-led households, are rentals. Some 54% of renters earn less than $50,000, and the annual median household income among renters is about $42,500, below the national median of $67,500, according to Zillow.

The problem is being felt around the world, too. A recent analysis by Bloomberg Economics found that 19 OECD countries have combined price-to-rent and home price-to-income ratios that are higher now than they were ahead of the 2008 financial crisis, indicating that prices have moved out of line with fundamentals.

Meanwhile, US landlords, including property investors snapping up a growing share of homes in metro areas, are gaining the upper hand.

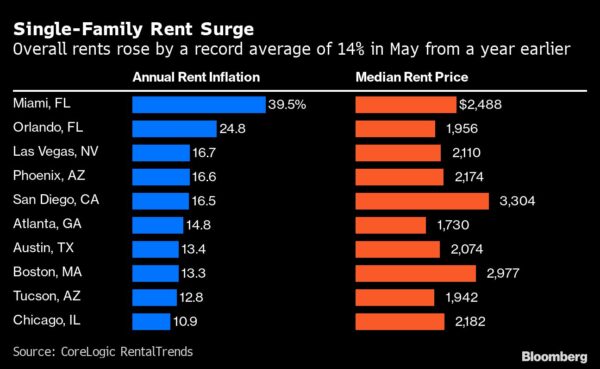

Single-family rents rose by a record 14% nationally in May from a year earlier, according to CoreLogic, a real estate data firm. The increases were even more dramatic in cities that became popular living destinations during the pandemic, including an almost 40% increase in Miami, a 25% rise in Orlando, Florida, and a 17% jump in Phoenix.

A coalition of tenant, community and legal organizations called on the Biden administration on Tuesday to declare a state of emergency on housing and find ways to regulate rents.

Some 5.4 million households, or 40% of households that are not current on their rent or mortgage payments, said they were likely to be evicted or foreclosed on in the next two months, according to a Census Bureau survey for June 29 to July 11. That is the highest share since the Census started asking the question in August 2020.

More renters than usual are staying put in their homes, sending apartment occupancy rates near the highest level in more than two decades, according to data from the property management software company RealPage. That cuts down on the number of apartments available for those looking to move.

But the imbalances are starting to improve. Close to 1 million rental units are expected to be added to the US market over the next year or so, which could ease some of the pressure, said Taylor Marr, deputy chief economist for real estate brokerage Redfin Corp.

Rent increases could drop to a range of 5% to 8% one year from now, he said. Still, it’s not clear when the market may return to the low single-digit increases more typical before the pandemic, putting continued strain on renters, he said. “We don’t expect dramatic shifts,” Marr said.

New Arrivals

An influx of new residents is driving up housing costs in Atlanta, where rents have increased 14.8% from a year ago as of May. The current median rent is $1,730 per month, according to CoreLogic. Major expansions in the area from tech giants such as Microsoft Corp., Apple Inc. and Google parent Alphabet Inc., are luring more high-paid tech workers. The city has also been a draw for people from higher-priced cities seeking less expensive options.

This January was the first time Karla Kelley was unable to renew the lease on her two-bedroom apartment in the Atlanta suburb of Duluth, Georgia, where she has lived since 2009. Her landlord decided to renovate, but gave her the option to move to a unit in another building, boosting her rent by almost $600 a month to $2,045. Kelley, 70, said she has noticed an influx of new residents from other cities.

“We’re getting a lot of people from the Northeast or from the West Coast,” said Kelley. “To them, these rents are not huge.”

Despite the higher price tag, she said the new apartment feels like a downgrade, with old carpeting and rusted light fixtures. “The night I got the keys, there were cockroaches running all around the apartment,” said Kelley. The air conditioning and faucets weren’t working.

Miami was also a big draw for remote workers during the pandemic, increasing competition for housing and pushing rents up by 40% over the last year, the steepest increase out of the 20 large metro areas studied by CoreLogic. The median asking rent in the city is now $2,488 per month.

Miami native Gabriela Noa Betancourt didn’t see her current apartment in person until the day she moved in. She and her partner began searching in June after the rent on their previous apartment increased by $650 to $2,400 a month. As they browsed listings, they noticed a pattern: Many of the units were being snapped up before they could visit. And the tours they did make it to were crowded, with dozens of other applicants.

“Things were just flying off the shelf,” she said.

It took a few tries to secure an apartment. Betancourt, 28, signed two leases for apartments in Miramar, Florida, but the landlord opted not to execute them, deciding instead to go with other prospective tenants who may have been willing to move in two weeks earlier. Their third lease finally stuck: a two-bedroom apartment in Southwest Miami-Dade County for $2,000. They lost about $100 in application fees.

Tough Choices

Las Vegas rents rose by 16.7% in May from the year prior to a median of $2,110 per month, the third largest increase out of 20 metro areas studied by CoreLogic data. After experiencing an oversupply of housing prior to the Great Recession, development in Las Vegas slowed before the pandemic, said Carl Whitaker, a director of research and analysis for RealPage. That created a mismatch when the city saw an inflow of residents from California and other parts of the West Coast, driving rents up, he said.

When Dennie Keener’s apartment rent in Las Vegas rose for the first time in over four years on March 1, his plan was to work extra shifts at his bartending job at the Dolby Live Theater. Seven days later, he was diagnosed with stage four pancreatic cancer and had to stop working. Now, he’s two months late on his rent and at risk of eviction. The monthly rent on his one-bedroom, 720-square-foot apartment rose to $1,000 from $750.

“I don’t have enough strength to work after my chemo,” he said. “At some point in my life, this terminal disease will kick in to where I can’t even work from a laptop.”

Keener, 58, used to earn about $6,000 a month, including tips. But he has now exhausted medical leave, and starting in August, his income will drop to $1,321 in monthly Social Security disability benefits. He has been looking for more affordable options, but he hasn’t been able to find anything in his price range. The Southern Nevada Housing Association is so saturated with requests for Section 8 housing benefits, a program that offers rental assistance to low-income households, that he cannot even register for the wait list.

In Tucson, Arizona, rents rose by 12.8% in May from the year prior, with the median rent price being $1,942 per month. Similar to Las Vegas, housing construction in Tucson slowed before the pandemic, worsening the rental shortage, Whitaker said. That led to more rent hikes after the city became home for more people moving out of Phoenix and California, he said.

Hana Cantral decided not to renew the lease on the one-bedroom apartment after her landlord upped the monthly cost. She worked out a deal to rent the guest house of a family friend for $750 a month, but the place will not be available until November. Until then, Cantral, 31, is staying on a month-to-month basis at her current apartment, and the rent keeps getting more expensive. Her bill rose to $727 from $640 in July, and is set to rise to $927 in August.

Cantral, who works doing Medicare appeals for an insurance company, is skipping her car loan payments and coping with interruptions to her water service. “Otherwise, I can’t pay my rent,” Cantral said.

Reynolds of the Urban Institute said she refers to this as the idea that “rent eats first,” which is when people put their money toward rent “even if it means that they can’t buy other essentials like groceries.”

Ballooning Debt

As rent, fuel and grocery costs rise, more people are turning to debt to cover their costs.

The Census survey from June 29 through July 11 found that about 30% of Americans said they used credit cards or loans to meet spending needs in the prior week, up from 23% in early January. And credit card balances jumped by $46 billion in the second quarter of this year, up 13% from a year earlier and marking the largest increase in more than 20 years, according to a report from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

Affording rent is often a stretch for Nancy Capron, a substitute teacher in Holyoke, Massachusetts. Capron, 56, typically earns between $12,000 and $17,000 annually, but she worked less than usual this year because of Covid-19. After her rent went up two months ago by $170, or nearly 30%, she is taking on more credit card debt to cover her bills.

It mirrors a pattern she used to stay afloat before the pandemic: accruing credit card debt throughout the year and then paying off a chunk with her tax refund. When she received enhanced unemployment benefits during the crisis, Capron did something that felt previously unachievable — she paid off her credit cards, clearing about $7,000 in debt.

Now, she estimates that the higher rent bill takes up close to 60% of her pay. She doesn’t blame her landlord, who explained that he is facing higher fuel costs and his real estate taxes went up after property values jumped during the crisis. But she is fearful that she may have to leave the apartment she’s called home for almost two decades.

In the meantime, Capron is searching for housing vouchers and considering looking for senior housing or another apartment with roommates.

“There is no place to live for anybody,” she said.

More stories like this are available on bloomberg.com.