By Arianne Cohen

In December 2019, a scandal erupted at Away, a luggage maker known for hard-shelled suitcases. Disgruntled workers at the company, then just four years old, complained publicly about working conditions, spurring a media investigation, which found that employees were expected to put in long hours, avoid taking vacation time during busy periods, answer messages on nights and weekends, and prioritize customer needs above all.

Broadly speaking, these are common—albeit imperfect—norms at many startups. “A startup is not a 9-to-5 job, period,” says Leslie Feinzaig, founder and chief executive officer of the women-focused venture firm Graham & Walker LLC. “These companies move fast and grow fast, and anyone who goes to work at one should expect a quick-moving environment, and like a challenge.”

Away’s female CEO at the time, Steph Korey, was publicly excoriated for creating a cutthroat culture, driven by her own round-the-clock work ethic. She stepped down temporarily, returned, and then permanently departed a few months later. A representative for Korey declined a Bloomberg Businessweek request for comment.

A study out in July sheds light on one of the dynamics that was likely at play: Employees, it turns out, do not expect female bosses to insist on long hours, and do not respond well when that extra work is requested. Even at startups. Olenka Kacperczyk, along with two other researchers, trawled through a decade of worktime data of almost 250,000 employees at more than 58,000 startups in Portugal and discovered that workers put in about 7% less overtime when the boss was female, and 1% less in regular hours. “In some ways it’s a very depressing finding,” says Kacperczyk, the study’s lead author, a professor of strategy and entrepreneurship at Imperial College Business School in London. “Even if we supply women with funding and put them through incubators or accelerators, there’s a bias on the part of employees that determines whether their new venture is ultimately successful.”

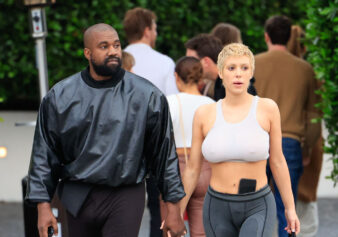

To dig into the matter further, they devised an experiment in which they hired online employees for a fictitious data analytics company, for work identifying executives in photos. At the end of the job, the fictitious founders asked the workers to do a bit of extra photo coding. When the request came from male owners, the workers mostly said yes. Women? The workers were more likely to decline, and even when they agreed, they did less. Notably, the tasks were accomplished equally well whether the boss was male or female, suggesting that only the amount of work for women lags, not quality.

Asked to explain their behavior, the photo coders in essence said that it’s OK to say no to a woman. “People feel more comfortable pushing back and saying, ‘Well, I have a family commitment, you must understand that,’” says Peter Younkin, associate professor of management at the University of Oregon’s Lundquist College of Business, who worked on the study. “With a man, they just assume that they have to say yes, and that male founders won’t understand work-life balance and will punish them in the future.”

Biases typically go unnoticed in individual day-to-day experience, and even when they’re apparent, companies tend to focus on the inequities they can both see and fix, such as gender pay gaps, says Isabelle Solal, an assistant professor of management at Essec Business School in Paris. She was not involved in the research and praised its “combination of real-world and experimental data, so we’re able to see a real management issue in context,” as well as its consideration of discrimination that flows from employee to boss.

Investors consistently ask female founders questions about their family planning intentions and grill accomplished founders about their capabilities—both experiences that male founders don’t share, says Amelia Suda, head of the leadership accelerator at Female Founders, a European community of 60,000 with well-known startup and leadership accelerators. The bias from below that the researchers identified was news to her. “My initial response was, ‘I can’t believe that this is coming from the employee level, too,’” Suda says. “Our female founders are really, really focused on culture and talk a lot about making sure that everyone has a reasonable workload and feels included, rather than, ‘Hey we’re just gonna work a lot.’”

The researchers say that women bosses everywhere likely face the same challenge. But the problem is particularly damaging to startups, where extra work is the lifeblood as small teams must accomplish large feats. Less productive employees accomplish less work, which can lower sales, profits, and long-term outcomes. “High growth is all about employees exerting this discretionary effort,” Kacperczyk says. Startup leaders have to be able to motivate their employees to work overtime, she says, with the understanding that the typical compensation structure involving equity for employees means that if the venture ultimately succeeds, everyone will reap rewards.