By Ella Ceron and Claire Ballentine

Student loan borrowers will no longer have any of their debt forgiven by President Joe Biden’s one-time relief plan after the Supreme Court voided the White House proposal.

That ruling comes just as a three-year pause on federal loan repayments is set to end. Borrowers who’d hoped for a more permanent reprieve are now trying to figure out where they can cut spending before those bills come due.

“It was too good to be true,” said Rudi Petry, a 31-year-old brand strategist in Durham, North Carolina. She has $95,000 of debt from undergraduate and graduate school, and was eligible for $20,000 in forgiveness. She said she won’t be able to afford her apartment when repayments resume, so she’ll have to move, and dreams of having a wedding and building a business will be put on hold.

The loans still make sense to her. “I saw myself as investing in myself — I needed that credential, and it worked, I got the job that I wanted,” she said. “But now I do have to pay the price. Now, it’s mentally starting from scratch again.”

The Supreme Court on Friday ruled 6-3 along ideological lines that the Biden administration’s effort to wipe $430 billion in student debt exceeded its power. “The question is not whether something should be done; it is who has the authority to do it,” Chief Justice John Roberts wrote in the majority opinion.

“The decision is very disheartening,” said Crystal Douglas, an occupational therapist and single mother in Michigan with $85,000 in federal student debt. The breathing space of forgiveness, when loan payments were also suspended, helped her pay for support services for her son at school. But with her finances already so tight even without the $300 she was paying monthly toward her student loans before the pandemic, figuring out what to cut back when her loan payments resume will be tough.

“Anything I can cut would be at my son’s expense so I can free up some financial space,” she said. “It just puts a lot of families at a disadvantage. We have to figure out what’s more important, our student debt or our families.”

For Alix Chronister, a 24-year-old in Kansas City, Missouri with $30,000 in federal loans, the worry now is managing repayments on her $50,000-per-year-salary. The $20,000 in forgiveness she was eligible for would have helped a lot, she says, but it’s “disappointing, mostly” that relief is once again out of sight.

“The most frustrating part is that I feel like, when it comes down to it, the billionaires will bail out banks but when it comes to helping the middle class, they’re like, ‘I’d rather not,’” she said.

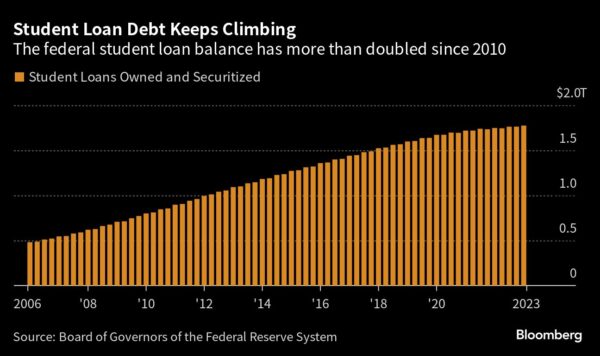

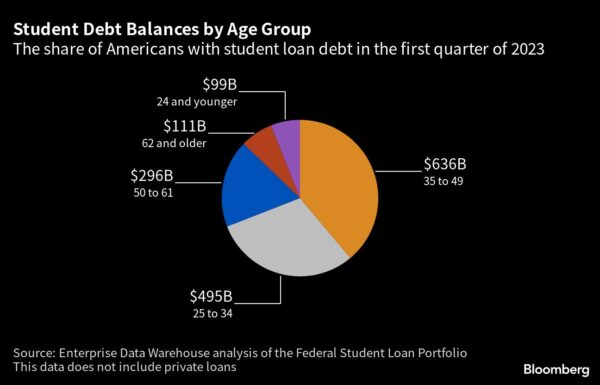

Student debt activists have long held that Biden should forgive part of the $1.8 trillion federal student loan balance some other way if the Supreme Court threw out his plan. The president is expected to announce new actions to protect borrowers later on Friday.

“Student loan relief is a promise from President Biden to more than 40 million families,” said Melissa Byrne, executive director of We, the 45 Million, a student-debt advocacy group. “It is our chance for dignity. He must immediately implement a plan B including finding a different path to ensure no repayment begins until cancellation is delivered.”

The White House had proposed $10,000 in student-debt forgiveness for borrowers who made less than $125,000 per year or $250,000 per year as a household. Those who had received Pell Grants when they went to school and met the income requirements were eligible for $20,000 in forgiveness. Before the White House paused the application portal in November, around 26 million people had applied.

An estimated 20 million with federal debt were expecting to have their balance completely forgiven under Biden’s plan. The Department of Education in a court filing last November warned of a spike in delinquencies and defaults when payments resume should one-time forgiveness not go through.

Coco Rowe, a 28-year-old in Las Vegas with about $20,000 in student debt, would have been eligible to have $10,000 forgiven. That would have been especially critical to her finances given that she was laid off from her artificial-intelligence job at the beginning of the pandemic, and hasn’t yet been able to find another full-time role.

“It was like a positive light in a time that was really hard for a lot of people and still is. It’s really disappointing that it was dangled in front of our faces and then taken away,” she said. “For my generation especially it was an expectation that you were supposed to go to college and then once you graduated you’ll get a good paying job and you can pay your debt. I was expecting having to pay it back, but if I could redo it, I don’t know if I would get a degree.”

More stories like this are available on bloomberg.com.