By Jonnelle Marte and Andre Tartar

Makayla Adams is living in the middle of an economic boom in South Florida. To her, it doesn’t always feel that way.

The guard at Port Everglades in Broward County was able to log close to 70 hours a week during the busy 2022 winter season for cruises, boosting her weekly pay to about $900 from roughly $500. And even though the county raised her hourly wage to $17 from $15 in January, her expenses — rent, child care, a car payment and car insurance — leave her with little disposable income.

“With that all getting paid on time, I have nothing to accommodate myself or my daughter,” said Adams, 22. “I’m taking care of my responsibilities, but it’s like I have no freedom.”

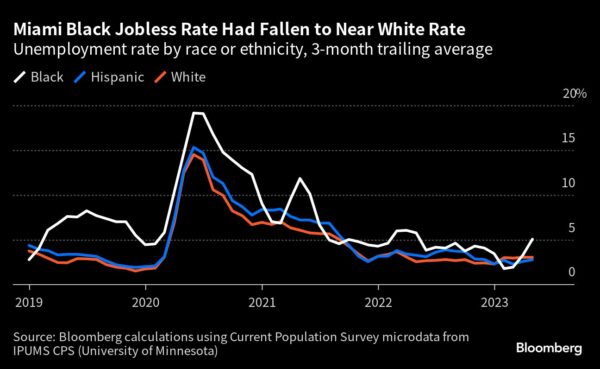

On paper, South Florida’s labor market has been great for Black workers like Adams. Miami has become the economic envy of cities around the US. That translated into what was record-low unemployment earlier this year for Black workers in the region, which includes Miami-Dade, Broward and Palm Beach counties, according to an analysis of government survey data. The unemployment rate for that demographic reached 5.1% between March 2023 and May 2023 — still one of the lowest among major US metro areas.

In reality, people of color are not benefitting equitably from the area’s boom. And they are also most vulnerable as the labor market cools, with Black workers accounting for 90% of the recent increase in unemployment across the country.

Much of the demand for labor in South Florida has been in leisure, hospitality and retail, where workers earning low wages are having a harder time keeping up with record rent growth and other rising costs. People of color in the region are almost three times as likely as their White counterparts to experience working poverty, which is when a family’s income is below 200% of the federal poverty level despite working full time, according to the National Equity Atlas, an online tool that tracks data on racial and economic inequities. That amounted to $39,440 in 2023 for a family of two, according to guidelines from the Department of Health and Human Services.

“What does it mean that there’s this kind of strong economic growth that we’ve seen?” said Abbie Langston, director of equitable economy at PolicyLink, a research institute based in Oakland, California. “It’s not that that’s bad news, but it’s not necessarily the full picture.”

While nearly 70% of South Florida’s workforce between the ages of 25 and 64 is Black or Hispanic, they are are overrepresented in jobs that tend to pay lower wages or offer fewer benefits, according to research co-authored by Langston and published in January by Florida International University in partnership with the National Equity Atlas and Lightcast with support from JPMorgan Chase.

The research also found that racial pay gaps persisted, even for Black workers with higher levels of education. White workers in the Miami area with a bachelor’s degree or higher earned a median wage of $32 an hour as of 2018, compared to $23 for their Black counterparts and $24 for Hispanic workers, the report found. The disparity is even worse among Black and Hispanic immigrant workers, only half of whom earn at least $15 per hour, compared to 80% of White workers.

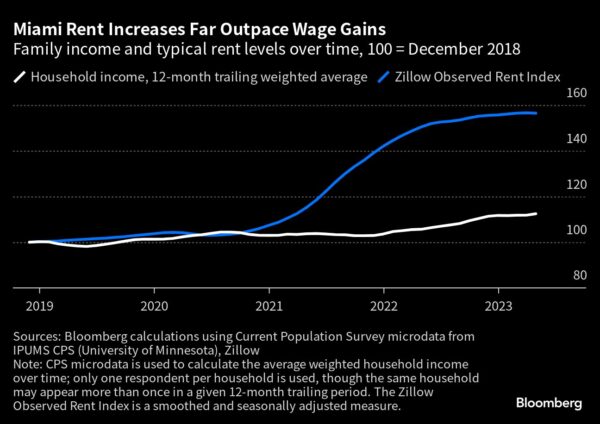

It’s all compounded by soaring rents in the city, which saw an influx of new residents thanks to a pandemic migration and an influx of companies from finance to tech. Miami is now the fourth most expensive city in the nation to rent a one-bedroom apartment following a 59% increase in rents since the pandemic, according to Zumper, a rental marketplace. That rent growth trounces the 23% rise in national median rents.

Miami and nearby Hialeah had the highest rates of rent burden among the largest 100 metros in the US, with 64% of households and 67% of households respectively spending more than 30% of their income on housing, according to PolicyLink. In Miami, 68% of Black households are likely to be rent-burdened, followed by Hispanic renters at 65%. That compares to 54% of White renters who are rent-burdened.

That increase in housing costs is largely the driving force behind Miami’s 6.9% inflation rate for the 12 months through June, compared to the 3% national rate seen in that time.

Deiango Emory has mostly been able to manage the increased cost of living — but is considering taking on a side gig delivering food to make extra money.

The 26-year-old made the move two years ago to a bakery in Wynwood, an artsy district in Miami known for its murals and outdoor bars. While his hourly pay initially went down to $15 from $17.50, he hoped the new job would offer more room for growth. He was right.

He is now making $18.50 an hour. And Emory, who sings and writes songs, says the shop also sells guitars and vintage cars, and is more in line with his creative interests. His hours are stable and he has fewer responsibilities than he did when he worked at a joint restaurant and coffee shop.

Over the past three years though, the rent he splits with a roommate has risen to $2,825 a month from $2,150.

“It’s gone up a lot because of all the New Yorkers who are coming who make a lot more than us,” said Emory. “Sometimes things get a little underwater, but mostly I’m managing.”

Read More: Super-Rich Escaping to Miami Are Insulated From Realities of Crime

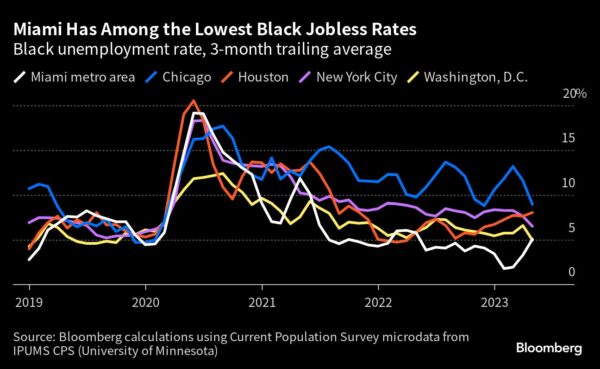

The picture has been different in business hubs such as New York City and Chicago, which have been losing residents and are suffering from a slower recovery in business travel and tourism, said Alí R. Bustamante, deputy director of the Worker Power and Economic Security Program at the Roosevelt Institute. The Black unemployment rates in Chicago, Houston, New York and Washington, D.C. had been double that of Miami’s earlier this year, and in most cases remain several percentage points higher.

“As a result of their slower recovery, they really haven’t had the underlying economic dynamics that really promote a really hot and strong labor market that brings a lot of Black Americans into good jobs,” said Bustamante.

Despite the disparities playing out across the country, Black unemployment hit a national all-time low of 4.7% in April, before ticking up to 6% in June. That’s the highest it’s been since August 2022.

Overshadowing those gains are questions about their lasting power. The Federal Reserve has been aggressively raising borrowing costs as part of its efforts to tame the strongest inflation in a generation. Many economists expect some job losses will be necessary for the central bank to achieve its goal of bringing the inflation rate back to its 2% target.

While the labor market has so far proven resilient, job gains are moderating, and some experts fear Black and Hispanic workers may face the brunt of the pain if and when the economy starts to turn, as is often the case during recessions. Bloomberg’s analysis found that across 14 key metro areas with sufficient data, Black and Hispanic unemployment rates rose between 1 and 3 percentage points more on average during the first several months of the pandemic than White jobless rates.

Miami’s workforce is projected to grow by 8% to 12% over the next decade, though just 41% of that growth is expected to be in good jobs, or those that pay enough to support a family of two working adults and two children, according to the research by National Equity Atlas. That figure was more than $35,000 in Miami as of 2019.

Unless racial divisions in the workforce change, the majority of those good jobs will be held by White and Asian or Pacific Islander workers. None of the 10 occupations expected to add the greatest number of Black workers are categorized as good jobs.

“We have these really longstanding, really thorny racial economic inequities,” said Langston, who estimates that shrinking racial gaps in employment and wages in the Miami region’s labor market would boost the local economy by $122 billion. “It’s actually a drag on economic growth.”

For Telecia Williams, even a recent promotion isn’t preventing her from living paycheck to paycheck. In December, her hourly pay before tips was boosted to $10 from $7, when she moved up from being a server to being a bartender.

But Williams, 37, is still earning only about half as much as she did before the pandemic when working at a posh restaurant in South Beach. Now that she has a daughter, it’s too far of a commute away from her daycare center.

Her bills are also more expensive now. Though Williams pushed back on her landlord’s attempt to raise her rent by $300 a month, she agreed to a smaller $100 increase in December — bringing the bill to $1,600. Her car insurance costs about $30 more a month after a discount expired, and many of her regular grocery items are more expensive.

“You’ve got to work double time just to pay to eat,” said Williams.