By Catherine Bosley and Michael Sasso

Consumers in Europe and the U.S. aren’t rushing to spend more than $2.7 trillion in savings socked away during the pandemic, dashing hopes for a consumption-fueled boost to economic growth on both sides of the Atlantic.

In the wake of lockdown easing during the northern hemisphere’s summer holiday season, excess savings in euro-area bank balances declined only marginally in August, and Italy still recorded an increase, according to calculations by Bloomberg Economics. In the U.S. there has also been no drawdown, the figures show.

The absence of a consumption surge that had been anticipated by some economists may speak against the prospect of a lasting inflation shock feared by central banks. While higher balances could help households cope with skyrocketing heating bills, tepid demand might temper businesses’ ability to push through permanent price increases.

“We’re not seeing any signs that the accumulated savings are coming back into the economy,” said Dario Perkins, managing director for global macro at TS Lombard in London. “Because people have these extra savings, they feel wealthy and they spend a bit more. A fraction of that money maybe gets spent, but it doesn’t come surging back.”

Bloomberg Economics calculates the total of excess savings built up since the crisis began at about $2.3 trillion in the U.S. and almost 400 billion euros ($464 billion) in the euro zone.

Although the European Central Bank has long cautioned the stock of money accumulated during lockdowns will remain “largely unspent,” corporate executives and economists were betting on a growth fillip.

What Bloomberg Economics Says…

“Households in the euro area have accumulated huge savings during the pandemic as spending plunged and governments supported incomes. While a consumption splurge looks unlikely for now, those savings will be a welcome buffer to some people as energy costs soar.”–Maeva Cousin, senior euro-area economist.

CaixaBank SA Chief Executive Officer Gonzalo Gortazar said in May that he expected some bunkered funds to fuel consumer spending. The OECD anticipated European consumption would benefit from “lifting of containment measures and the concomitant fall in households saving, which finances sizable pent-up demand.”

The data throw cold water on the theory of a broad-based rally.

European Commission sentiment gauges don’t indicate a boom in major purchases, and U.K. numbers also show consumers are cautious and unusually eager to save. In the U.S., the world’s biggest economy, consumer sentiment slumped during the summer.

Anecdotally, some spending did increase. Jeweler Pandora A/S said its U.S. business got a fillip from pandemic stimulus checks, while U.K. retailer Next Plc noted in September that “the combined effect of pent-up demand for clothing, record savings ratios, and far fewer overseas holidays” boosted sales, though the effect was likely to diminish.

Among reasons people have held on to their money are anxiety about resurgent outbreaks, the pace of the recovery and job prospects. Demographics and consumption patterns may also play a part.

Deutsche Bank AG analyst Olga Cotaga reckons that because people can’t recoup missed spending on services once a lockdown ends, that means they don’t consume enough to make a dent in their savings.

“We just get one haircut — we don’t get the amount of haircuts we missed during lockdown,” she said in a Sept. 21 podcast. “That pent-up demand that’s the backlog of all the decisions that you postponed during lockdown isn’t really there.”

Consumer preferences have also changed for good, according to an ECB paper that found many people realized during 2020 that they just didn’t miss certain things.

Some savings depletion is still helping to sustain the economic rebound, according to Karen Ward, chief market strategist in EMEA at JPMorgan Asset Management.

“The tail winds for demand are pretty strong,” she told Bloomberg Television. “I don’t think what we’ve seen so far is going to derail the recovery.”

Even so, shortages of goods amid a global supply squeeze mean that sometimes where there’s demand, money can’t be spent.

In suburban Minneapolis, financial adviser Mike Leverty says his affluent clients want to dip into savings to buy new cars or swimming pools, but can’t because of shortages of goods or labor.

“A client wants to do a kitchen remodel, but the contractors are booked for a year,” he said.

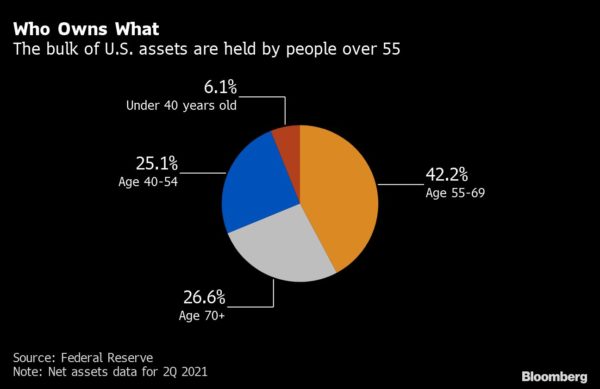

Finally, the vast pile of money also hasn’t accrued to all socio-economic groups equally. Seniors and the already wealthy have experienced the biggest gains — but they are often the least likely to spend.

“My sense is that much of that savings has accrued to upper middle income and upper income households,” said Mark Vitner, an economist at Wells Fargo & Co. “I think there’s still plenty of fuel in the tank.”

More stories like this are available on bloomberg.com.