By Matthew Boyle

Business schools can’t stop talking about diversity these days. Every institution, it seems, has issued thoughtful statements or disclosed ambitious plans around advancing racial equity. But when asked to disclose the diversity of their professors, an uncomfortable silence ensues.

Some simply don’t know. Others might know, but won’t say. A few skew the results by including visiting staff or lecturers in addition to the tenured and tenure-track faculty that really matter. When the numbers are available, they’re abysmal. Which raises the question: How can American B-schools prepare an increasingly diverse student body to succeed in an increasingly multicultural society with teachers who are anything but?

When it comes to the racial and ethnic composition of MBA students, Bloomberg Businessweek’s inaugural Best B-Schools Diversity Index shows they’re more diverse than a decade ago. From 2011 to 2021, the percentage of Hispanics enrolled in U.S. MBA programs doubled, according to the Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business (AACSB), and there are more Black and multiracial students as well.

But the combined share of Black, Hispanic, and Native American full-time B-school professors has barely budged, going from 5.4 percent to 7.2 percent over the past decade. (Asians make up 19 percent of faculty, up from 14 percent in 2011 and well above their 6 percent share of the U.S. population.) At many top programs, you can count the underrepresented minority professors on your fingers—and still have a few digits left. Carnegie Mellon’s Tepper School of Business has zero Black faculty. Dartmouth’s Tuck School, two. At the University of Washington’s Foster School, it’s “less than 1 percent,” a spokeswoman says.

As sad as those schools’ numbers are, at least they owned up to the problem: Pennsylvania’s Wharton, NYU’s Stern, Columbia Business School, Cornell’s Johnson, and the University of Chicago’s Booth—all in the top 20 of Bloomberg Businessweek’s overall ranking of MBA programs—declined repeated requests for figures. Wharton and Booth said they had data only for the university overall, not the business school. The others declined to comment or said they don’t have the data.

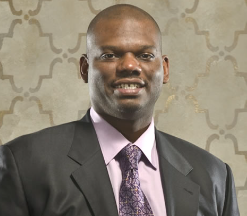

“I went to business school in the 1980s, and there wasn’t a diverse faculty,” says Kirk Holmes, a former president of the Black Alumni Association at Stanford University’s Graduate School of Business and a member of the school’s alumni racial equity task force. “Here we are in 2021, and it’s about the same. That’s very disappointing.”

In 1994, a small group of corporate and higher education leaders embarked on what they called the PhD Project. The goal was to persuade underrepresented minorities—who at the time made up about 1 percent of B-school faculty—to leave lucrative private-sector careers and pursue a doctorate in business, typically required for a tenure-track teaching role. The PhD Project offers candidates guidance on applications, research, fellowships, and the tenure process. With the expanded pipeline, the number of minority business school professors has increased from 294 to 1,387 since the project began (out of about 30,000 total U.S. faculty), and there are 277 doctoral candidates currently enrolled through the project (out of about 7,000 total).

There’s no denying the impact of having more people of color at the front of a classroom: It inspires minority students, and research has shown that faculty of color use a wider variety of teaching techniques than their white colleagues, enriching the experience for everyone. But expanding the pipeline is only part of the solution, since many schools’ faculty recruiting committees suffer from unconscious bias because of their lack of diversity. These groups mostly want to hire from leading programs, but since few minorities go to top schools, it’s harder for them to get published in top-tier journals, which makes it tougher to get hired by the top schools.

The decentralized nature of higher education means university-wide diversity policies don’t always trickle down to the business school. And even if they do, some departments can simply ignore them. “When you have 100 faculty and everyone owns 1/100th of the responsibility, the need to do something dissipates,” says Laurie Girand, a Stanford MBA and former Silicon Valley marketing manager who’s now a social justice advocate.

A common tactic, installing a chief diversity officer, isn’t enough. Those roles too often lack real authority over faculty hiring and sometimes require juggling of classroom and research responsibilities, too. Carolyn Yoon, for instance, was recently installed as associate dean for diversity, equity, and inclusion at the University of Michigan’s Ross School of Business, where she’s also a full marketing professor.

“To be honest, I wasn’t sure if I had the stomach” for the job, she admits, as the school’s Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DE&I) office was frequently “in crisis management mode.” It didn’t help that when she first asked full-time faculty to list something they did to support diversity as part of their annual evaluations, only one out of four bothered to answer. Now most respond, but the composition of Ross’s 129-person full-time faculty hasn’t changed much, with just five professors who identify as Latinx or African-American, up from four in previous years.

“All of us want more diversity, but when it comes to actual behavior and the way the system is set up,” Yoon says, individual departments will say they simply “go after the best candidates. Someone else can worry about diversity.”

That someone else is usually an overworked minority. “For faculty of color, efforts to address inequity are often expected to be their responsibility,” marketing professors Sonya A. Grier and Sonja Martin Poole write in their article “Reproducing Inequity: The Role of Race in the Business School Faculty Search.” They call B-schools irresponsible for not prioritizing racial diversity and report that Black and Latinx faculty are often tapped to join DE&I task forces or hiring committees while also mentoring minority students and junior faculty.

“They are committeed to death,” says Alisa Mosley, the provost and senior vice president for academic affairs at Jackson State University, who calls the additional burdens a “Black tax.” Mosley knows how hard it can be: When applying for a job at the University of Arkansas in the late 1990s, she was mistakenly copied on an email in which faculty debated whether she would “fit in,” which she interpreted as “a very loaded statement.” A University of Arkansas representative declined to comment on the event but said its Sam Walton College of Business has had a diversity and inclusion office since 1994 and “actively” recruits diverse faculty.

Change won’t happen until schools acknowledge and embrace less traditional paths into the ivory tower, with less emphasis on recruiting only from top-tier programs. “We tend to look only in particular areas,” says Srikant Datar, dean of the Harvard Business School, where 5 percent of the 293-person faculty (including visiting teachers) last year identified as African-American or Latinx. “It turns out that the more you broaden the funnel, the more you can do.”

There are signs of progress: Harvard B-school faculty hired over the past year are the most diverse group ever. Before the academic year even started, Datar sat incoming professors down with Black faculty “to begin making connections.”

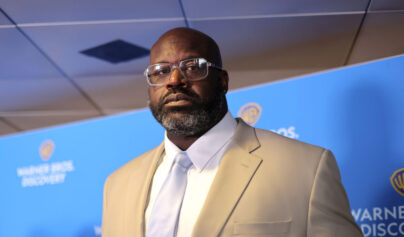

Discussions of what diversity really means and what it entails are uncomfortable but necessary, says Miles Davis, an early member of the PhD Project. “A lot of folks don’t even know how to have these conversations,” says Davis, who in 2018 became president of Linfield University in Oregon, the first PhD Project participant to reach that level. “You have to change the way you do things. I would challenge business schools to rethink what leadership looks like. These challenges are everyone’s challenges.” Read next: How 15 Best Cities for Business in the World Rank for Gender Equality

More stories like this are available on bloomberg.com.