By David Voreacos

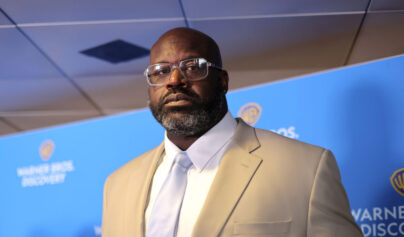

Gary Harmon grinned as he lounged in a bathtub full of dollar bills surrounded by scantily clad women. The moment, captured in a photo on his cellphone, could be part of his undoing. To US prosecutors, it’s evidence that he suddenly came into a lot of money.

The prosecutors accuse Harmon of a very unusual crime: remotely swiping Bitcoin stored on a computer device the government had already seized in another case, brought against his older brother, Larry. As authorities watched helplessly, 713 digital tokens—then worth almost $5 million—were somehow spirited away from the “hardware wallet” they were holding in an evidence locker.

Larry Harmon, who’s since pleaded guilty to laundering $311 million through crypto transactions, swore up and down he wasn’t involved in the disappearing act. Instead, Larry, 39, pointed the finger at Gary, 30, and ultimately helped to nail him. Gary is in federal jail in Washington, D.C., awaiting trial, and Larry is free on bail near Akron. The cases of the Harmons—literal crypto bros—show how the IRS and the FBI are succeeding in collecting evidence but still face challenges on the blockchain frontier. Authorities had to track digital money moving through a tangle of anonymous accounts to connect it to Larry. When they tried to seize it, they faced a problem: How do you put a fence around a quicksilver asset such as Bitcoin?

Larry’s arrest in February 2020 was something of a milestone in crypto enforcement. In addition to the large sums of money involved, it was the first time anyone had been charged with crimes related to “mixing,” a practice that makes it much harder to trace transactions by jumbling together tokens from different owners. In 2014, Larry created a search engine called Grams, which helped users scour the darknet for illegal drugs, guns, and hacking services. Then users could pay via a mixing service he ran called Helix, earning Larry 2.5% of each transaction.

Mixing’s advocates in the crypto world say it enhances privacy. But under the online moniker “gramsadmin,” Larry touted Helix as a way to prevent law enforcement from tracing tainted Bitcoin.

Business took off. In late 2016, AlphaBay, then the largest market on the darknet, started steering its customers to Helix. US authorities were watching. An undercover FBI agent transferred Bitcoin from AlphaBay to Helix, establishing a link between them. In July 2017 the US shut down AlphaBay, calling it a major source of heroin and fentanyl. Authorities didn’t yet know who ran Helix. Months later, Larry closed down the mixer, having performed 356,000 Bitcoin transactions. More publicly he developed Dropbit, an app he promoted as the Venmo of crypto for transfers between users. Larry was a tireless promoter of Bitcoin and his company Coin Ninja. In a 2019 video on Twitter, he showed off his Bitcoin hat, shirt, and socks.

The US hunt to identify Helix’s operator picked up when IRS criminal agents joined the case. Bitcoin transactions are executed on a blockchain, a publicly viewable online database. The coins move between accounts with no names, just long strings of random-looking letters and numbers. Crypto transactions may seem free of fingerprints, but they often can be tracked down when individuals try to turn coins into cash. That’s where Larry made some mistakes.

Working with Chainalysis, a blockchain analytics company, the agents studied thousands of Helix transactions, subpoenaed emails, and ultimately found one involving a website that allows users to buy gift cards with Bitcoin. An email associated with Larry was used to open the account, says a person familiar with the matter who wasn’t authorized to discuss the case publicly.

Agents built a detailed financial picture of Larry. Inspecting his cloud accounts, they found a Google Glass photo of a computer screen showing the Helix administrator page. In early 2020, agents arrested him at his Akron office, where they also found a Trezor crypto storage device, a small computer attachment that looks a bit like an MP3 player.

Gary lived across the hall from the office. He talked to agents that morning and attended the hearing where prosecutors convinced a judge that Larry was a flight risk and should stay locked up. Larry was moved to a Washington jail, but when Covid-19 exploded, his lawyers sought his release on bail. Among the letters of support was one from Gary, who wrote effusively about Larry’s positive influence on his life, saying his older brother had given him a job, taught him coding, and “truly made me a better person.”

At the bail hearing on March 13, 2020, Assistant US Attorney Christopher Brown said Larry had “potentially tens of millions of dollars” in crypto assets that were illegal proceeds. Agents couldn’t gain access to them from the storage device found in his office because they didn’t have the correct passphrases to unlock them. But they could see, looking at the blockchain online, that addresses they had traced back to Larry controlled the money.

Hardware crypto wallets hold the cryptographic private keys—long strings of numbers and letters—that allow someone to go online and use a Bitcoin address for transactions. As a backup, Trezor hardware wallets can generate a “seed phrase,” a combination of as many as 24 words that can re-create those private keys on another device. In essence, anyone who knows the magic words and an additional PIN can take control of the Bitcoin. Unplugging the wallet device and physically locking it away is no protection. Brown warned that Larry could remotely take Bitcoin and that the government would be powerless to stop it. “Until we can secure them and transfer them to a government wallet, those are available for him or his family members to transfer,” he said in court. US District Judge Beryl Howell granted bail anyway.

Over six days in April 2020, IRS agents discovered Bitcoin was moved from the addresses they knew about. Prosecutors went back to court. Howell said she was “very skeptical” that the crime had occurred without Larry’s knowledge and direction. “Do you understand that?” the judge asked. “Yes, I do know,” Larry said. “Don’t try and be cute with me,” the judge snapped.

Howell ordered Larry to turn over all his passwords so agents could transfer the remaining 4,164 Bitcoins—then valued at $40 million—to a secure wallet. Larry did, and the thefts stopped. He continued to deny any role in the caper, but if it wasn’t Larry, who was it?

Within a month, Larry told prosecutors that Gary was the culprit, as did an informant. It took prosecutors 15 more months to get Larry to plead guilty to money laundering and agree to provide evidence against Gary and darknet operators. Larry faces up to 20 years in prison, but his cooperation with prosecutors will likely earn him a lesser sentence. He’s also been hit with a $60 million civil fine from the US Department of the Treasury.

Federal agents began building a case against Gary. An informant told them Gary had asked his advice on Bitcoin gambling services, records show. The source believed Gary wanted to use them to mix Bitcoin he took from Larry. Gary is “not the sharpest tool in the shed and did not think through the consequences for his brother” before he moved the Bitcoin, the informant said.

Agents later found four emails sent to Gary’s Gmail account from [email protected], reflecting the re-creation of wallets on devices. He’s denied taking the Bitcoin. When agents interviewed him in July 2020, he said, “If I took it, why wouldn’t I take it all?”

Recently, Gary’s lawyer said in court that “just because the government cannot manage to keep up with its technology, that is not the defendant’s problem.”

The government says agents traced 519 of the stolen Bitcoin through two mixers. Although the mixing hides where the money went, prosecutors say the transactions correspond to a “dramatic transformation” in Gary’s finances. They say he deposited 68 Bitcoin with the BlockFi finance company, which lets people borrow against their coins. He used most as collateral for a $1.2 million loan. Some of that went to buy a luxury condo in Cleveland, prosecutors said. And then there was the picture on his phone, included in the government’s court filings, of the bathtub of bills.

Gary was arrested in July 2021, accused of money laundering and other crimes. Like his brother, he requested bail. Prosecutors said to secure bail Gary should have to turn over seed phrases to the stolen Bitcoin. His lawyer said that condition would force him to admit crimes, which violates his Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination.

At a hearing in July, prosecutor Brown said Gary turned down two plea offers. His trial is scheduled for February.

More stories like this are available on bloomberg.com