Patricia E. Jones is on a journey to preserve her family’s legacy and their 40-acre stretch of Hazlehurst, Mississippi, farmland. She is also using the property to make a case for reparations.

In addition to restoring the property, she also hopes this project will help encourage a case for reparations. But for now, Jones’ goal is to turn it into a healing space for creatives of color in need of a place to work, network, and destress. She hopes to make her great grandparents’ home the retreat’s main office.

Jones’ family has managed to retain the land since 1880. The Jones family started their journey as enslaved people but managed to transform their legacy even though they started with so little. Many of the Jones family members went on to attend college and pursue trade school education.

“I don’t think I’d be alive had we not had that land to set foot on right out of slavery,” Jones told MarketWatch.com. “My ancestors who got the land at first were both born enslaved people, and they were able to use that land to farm cotton, have many children, support themselves, and try their best to catch up financially.”

Home and Heritage

Jones’ great-grandfather, Rev. William Talbot Handy, was born on the coveted property three decades after the Civil War ended. He joined the Tuskegee Quartet and even sang at Booker T. Washington’s funeral. He used his labor job in Copiah County to put himself through the Tuskegee Institute.

Jones’ great-grandfather went on to have his children in New Orleans, which included Dr. Geneva Handy Southall and Antoinette Handy. Southall was the first woman to get a Ph.D. in piano performance, and Antoinette was a Richmond Symphony flautist. The Jones family is also filled with activists, academics, and artists.

“We have a whole history of ministers, teachers, artists, entrepreneurs,” Tisch Jones, Jones’ mother, a University of Iowa professor emerita and a civil rights activist, told MorningStar.com. “This land allowed that to happen, which is why I fight for reparations so much. This is an example of what would have happened if we had received our 40 acres from the beginning. We received it. Look what has happened to our family as a result of land ownership.”

Forgotten Land

But the land at some point was abandoned, although, unlike many other Black families, it was still in the family’s possession.

Many Black families in the South, Jones’ family ventured north for better jobs, leaving behind their now-coveted acres.

Many Black famers and landowners faced discriminatory lending practices leaving them without means to obtain capital. This “contributed to foreclosures and tax sales; people involuntarily lost inherited property through partition sales and clouded titles, often stemming from the lack of access to estate planning that made Black families so vulnerable,” Market Watch reports.

According to government data, in 1910, Blacks operated and owned more than 2.2 million acres of Mississippi farmland. By 2017, that number dropped drastically to less than 400,000 acres.

In some cases, the poverty was seized by the government through eminent domain. In other cases, some Black failed were forced to abandon property due to violence and intimidation.

Jones was lucky the land stayed in the family, even if forgotten.

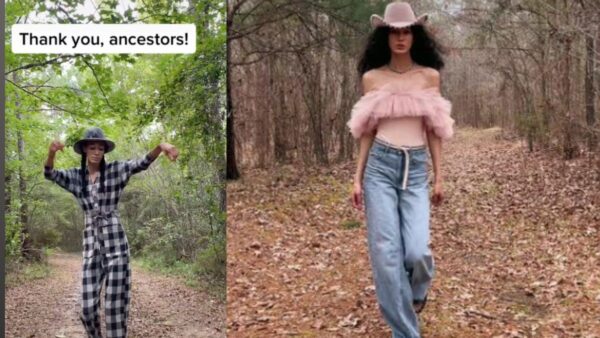

Today, Jones is working to rrestore her family’s property, which she’s documenting via TikTok and Instagram. While the property had been vacant for years, and she looks at her restoration journey almost as a form of reparations and an opportunity to correct institutional wrongdoings.

In Jones’ content, she gives viewers a look into her family ancestry through audio records, photos, newspaper clippings, and more factual details.

“My great-grandfather was a minister, and in 1932, Albert Einstein visited his church,” she says in one TikTok. She also shared how her great-great-grandmother was listed as a “servant” on the 1880 census. Her restoration process on social media currently has millions of views.

Restoration Journey has been expensive

In Early 2022, Jones set up a GoFundMe campaign to raise $60,000, but has raised only a quarter of that goal. A family member contributed about $60,000 in belongings, funds and a gazebo in February. Jones has also run through her personal savings as well as money left in the trust by her great-grandmother for a total of about another $60,000.

As part of restoring the land, Jones and team are restoring a 150-year-old house her great-grandparents built on the land. She is documenting the contraction work on her TikTok account.

“I believe all Black people need land access, because we worked the land in this country and built the economy we have today,” Jones told MarketWatch. “We need this space. We need the space to rest, we need the space to grow, we need the place to learn. We need a safe space.”

Inspiring young woman…Mississippi is due for an overhaul of young and gifted moving back.