Connecticut elected officials are reigniting a national legislative bill that would help close the wealth gap in the United States. This summer, Connecticut launched CT Baby Bonds Program, providing a trust for children born into poverty and whose births were covered under Medicaid programs.

The state will hold the money in an interest-bearing account until children turn 18. The funds are available to purchase a home, for educational purposes, or to start a business in the state.

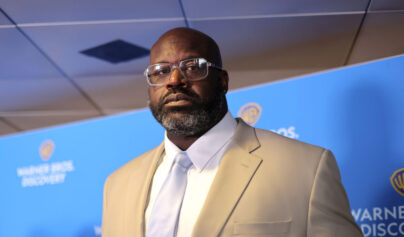

“Connecticut is ground zero for wealth and income inequality,” said Shawn Wooden, Connecticut Treasurer. “I hope that the federal government and other states follow our lead. CT Baby Bonds can be a model to help narrow the racial wealth gap across the country.”

The state is pushing for a legislative bill sponsored by Democratic Sen. Cory Booker of New Jersey and Massachusetts Democratic Rep. Ayanna Pressley in 2017. The federalAmerican Opportunity Accounts Act bill would fund a savings account of $1,000 at birth for children born below the poverty line. The federal government would provide annual deposits to children of up to $2,000, with the benefit gradually decreasing as household income increases. Under proposed bill, if a family of four has a household income less than $25,100, the children receive the full $2,000, but a family of four with a household income of $125,751 or more would receive nothing.

Like Connecticut’s program, the proposed funds would be placed in an interest-bearing account that can be used for specific reasons.

The federal proposal would offer a $50,000 maximum investment per bond.

New York City, meanwhile, introduced its own baby bond program this summer for kindergartners. The program will put $100 into a 529 plan for each student. A 529 plan, legally known as “qualified tuition plan,” is sponsored by states, state agencies, or educational institutions as a tax-advantaged investment.

Baby Bonds: One Term, Two Meanings

When financial advisers and investors refer to baby bonds, they define a bond with a value of less than $1,000. The purpose of these bonds is to attract investors who cannot invest large amounts of money in a traditional bond. The most common baby bonds are issued by municipalities or as savings bonds issued by the government.

However, the reference to baby bonds can also refer to government policy — on the state or federal level — of providing children with a publicly funded trust account when they are born.

Will Baby Bonds Help Close the Wealth Gap?

Often, when we think of wealth, we consider financial status. But what makes that status possible? Access to education, homeownership, and seed funds to launch a business are among the things that help accumulate generational wealth. The Urban Institute reports that parental income and level of education greatly inform a child’s ultimate socioeconomic class.

Over the past few decades, wealth inequality has significantly increased in the U.S. And wealth inequality impacts people of color at a higher rate than white Americans. According to economist Edward Wolff, a professor of economics at New York University and a research associate at the National Bureau of Economic Research, the median African-American household has a $3,400 net worth, compared to $140,500 for the median white household.

Support for baby bonds as a policy initiative has been based on several reports arguing that such trusts could help close the wealth gap in the U.S. A 2019 study conducted by Columbia University and McKinsey & Co. highlighted the importance of baby bonds. McKinsey noted that not closing the racial wealth gap could cost the U.S. economy an estimated $1 trillion to $1.5 trillion over the next ten years.

Are Baby Bonds a Form of Reparations?

Many also wonder if baby bonds can be considered reparations since it is looking to develop equality for people of color who disproportionately lack access to wealth-building assets.

Yet lawmakers contend that the national bill, along with the bill just passed in Connecticut, should not be considered reparations as it benefits all citizens below the poverty line.

According to preeminent reparations scholar William “Sandy” Darity, director of the Samuel DuBois Cook Center on Social Equity at Duke University, they can help close the wealth gap, but the only way to truly close the gap is through reparations. In 2019, Darity tweeted, “Baby bonds, in its current forms, would close about 20 percent of the racial wealth gap. Why are you fixated on non-reparations solutions to closing the racial wealth gap?”

Darity, who co-authored the book “From Here to Equality: Reparations for Black Americans in the Twenty-First Century” with A. Kirsten Mullen, added, “Since ‘baby bonds’ are paid out to each newborn cohort of infants, anchored on the median household’s wealth, it simply cannot close the racial wealth gap in the short or long term — unless white wealth collapses entirely.”