By Jordan Yadoo

Carnissa Lucas-Smith is more than a year into what she hopes will be a long legal career. If it hadn’t been for Covid-19, she would’ve had another hoop to jump through first.

After graduating from New York University School of Law, the next goal for Lucas-Smith was to work as a public defender in her native King County in Seattle, where she’d interned the previous summer. Any other year, that would have required passing a two-day, 12-hour exam—after completing a $3,000 preparatory course—to qualify for the bar.

But Washington was one of four states to waive that requirement for the pandemic-challenged class of 2020. It was an unprecedented if temporary move, one that’s triggered calls for permanent changes that can open entry paths to an elite profession for a wider group of candidates.

The Covid crisis has reignited a debate over what kind of credentials are really essential for American workers, and which requirements could be ditched at a time when job openings are at historic highs.

It’s happening in the public sector—Maryland just scrapped college-degree requirements for thousands of government jobs—and the business world, where giants like IBM Corp. have been taking similar steps. Colleges are reexamining their criteria, too: Many have dropped compulsory entrance exams.

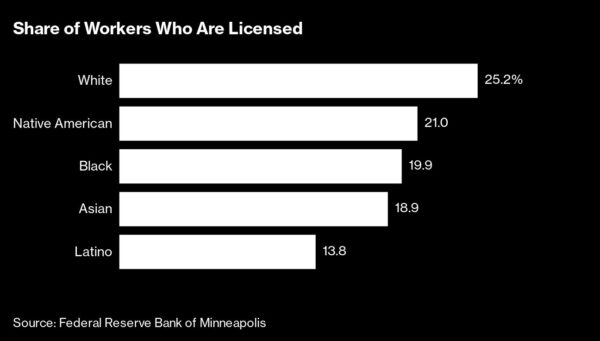

Some of the changes are driven by a reckoning with racial exclusion. What’s sometimes called “credentialism” tends to hold back Black and Hispanic job applicants the most, according to a study released last month by the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. There’s also the work-from-home revolution: Swaths of the economy have moved online in a way that cuts across state regulatory lines.

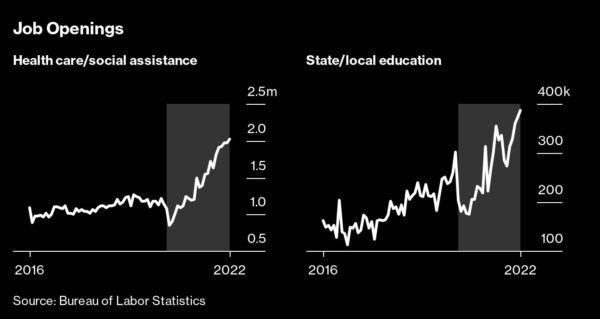

And behind all of this lies a labor shortage that’s left hospitals and schools, for example, struggling to find staff—and that may persist after the coronavirus has been contained. Government projections for the coming decade show the slowest labor-force growth in recent history.

“The relaxation of occupational licensing requirements has really occurred in large part because of the pandemic,” says Morris Kleiner, a professor of labor policy at the University of Minnesota.

It’s pushing up against a trend that’s played out over decades. In the 1950s, about 1 in 20 Americans needed a license to work in their field, and now it’s about 1 in 4.

The Biden administration is keen to reduce the red tape. In an executive order last year to boost competition, the White House said licensing “can impede worker mobility without countervailing benefits,” and encouraged the Federal Trade Commission to ban unnecessary requirements. A Treasury report in March called for a review of licensing criteria to make more workers available.

The debate about the costs and benefits of licensing, which used to revolve around lines of work like hairstyling and plumbing, has widened to include professions such as law and teaching. Another place where Kleiner—co-author of a 2018 paper that found licensing costs the economy almost $200 billion a year in “misallocated resources”—sees change under way is medical care.

More than 20 states sped up certification processes for inactive or retired physicians because of pandemic staffing gaps. A similar number waived licensing requirements for telemedicine.

In the legal profession, it was technical challenges over administering the bar exam that persuaded Washington and three other states to allow graduates of accredited law schools in 2020 to skip it. There’s an underlying shortage of public defenders, too, with trials delayed and court systems under strain as a result.

“The whole bar process is just a big ball of anxiety,” says Lucas-Smith, who worried about catching Covid before the exam and being unable to study—or being infected while crammed into an auditorium with hundreds of candidates.

Now she mostly works with families in the foster-care system, and sometimes children who arrived in the U.S. as unaccompanied minors, and says not taking the bar test hasn’t affected her ability to help them. “There’s so much of the bar that I was studying that’s completely inapplicable to my job,” she says.

The bar exam has been a higher hurdle for lawyers from minority backgrounds. The American Bar Association says 66% of Black candidates and 76% of Hispanics passed on their first try in 2020, compared with 88% of White test-takers.

Even though the four states subsequently reintroduced the exam, there’s new momentum behind efforts to get rid of it. The Oregon Supreme Court in January backed a proposal that would allow graduates to opt out of the test and become licensed via work experience or supervision instead.

The pandemic and the social justice protests that spread across the country in 2020 “really accelerated this conversation,” says Deborah Jones Merritt, a professor at Ohio State University’s Moritz College of Law. The exam would be “struck down as illegal” if it were an employment test, she says, because of the racial disparities.

Public schools are another place where labor shortages worsened in the pandemic, forcing recruiters to broaden their net. Payrolls in local education were down by more than 330,000 in March compared with pre-pandemic levels.

“We want to make sure that we prioritize talent over credentials in this moment,” says Thomas Toch, director of FutureEd, a think tank at Georgetown University’s McCourt School of Public Policy. “There’s a lot of untapped talent out there.”

One way school districts can respond, he says, is to widen their recruiting net—for example, bringing in local artists, foreign-language speakers, or science and math specialists as substitute or part-time teachers.

Ohio has made it easier to recruit teachers with expired licenses. New York’s education department is seeking to simplify certification processes. Boston’s public schools superintendent urged the U.S. Department of Education to set up a national licensing system that would make it easier for teachers to move from state to state.

The case for credential regimes invokes the need to protect public health and safety—a powerful argument when it comes to medical care, courts, or schools, where everyone accepts the need for high qualification standards.

The American Medical Association has fought back against proposals for nurses to carry out some kinds of treatments currently limited to doctors—and nurses have opposed allowing less-qualified home-health workers to expand their scope. The National Conference of Bar Examiners argued in 2020 that the bar exam ensures “the public is served by competent and ethical lawyers.”

Lucas-Smith says it functions more like a gatekeeping measure, blocking access for people with lower resources, and hopes it ends up getting scrapped for good.

“It’s not actually testing if you’ll be a good lawyer,” she says. “It’s just testing if you can memorize a bunch of random facts.”

More stories like this are available on bloomberg.com.