By Prashant Gopal and Catarina Saraiva

In an American housing market that for years has been plagued by too little inventory, builders are suddenly finding themselves with a glut of unsold homes.

This year’s surge in mortgage rates tossed buyers to the sidelines. The waitlists for new houses are gone. And new-home sellers such as Kevin Brown, who works just south of Houston, are on the front lines of a massive shift.

While Brown used to have back-to-back appointments, buyers now just trickle in to his Saratoga Homes sales office. Meanwhile, he’s got 55 houses under construction and five that are complete, all without deals.

“There’s a bit of pressure on us,” Brown said. “Builders have got to hit goals and make their profit, and they don’t like inventory just sitting on the ground.”

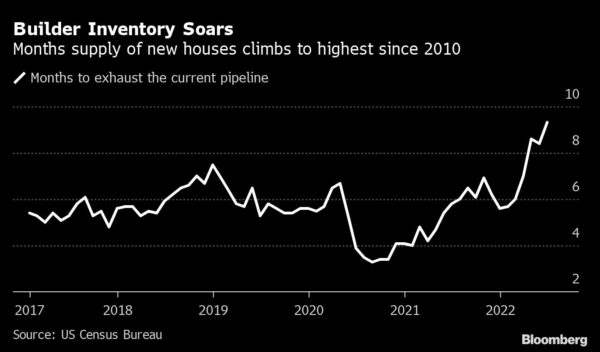

An abrupt halt to the pandemic housing boom has left builders that started construction months ago scrambling to adapt. The US supply of new homes relative to sales in June was the highest since the midst of the last crash in 2010. And by early July, buyer traffic to homebuilder websites and sales offices had plunged to the lowest level for the month since 2012, according to a survey of builder sentiment from the National Association of Home Builders.

The new-home pile up underscores a broader shift that’s wreaking havoc in the market. A national housing shortage contributed to years of bidding wars and desperation among buyers who bid up prices to record levels for fear of missing out. But this year’s surge in borrowing costs has now pushed affordability to a breaking point and eased some of the scarcity.

At the same time, the stage is set for longer-term supply constraints as builders pull back. A decade of underbuilding and a bulging population of young people aging into homeownership threatens to prolong the affordability squeeze.

“Despite the fact that there aren’t enough housing units in the country, builders are not willing to take the gamble that’s required to build them,” said Jerry Howard, chief executive officer of the homebuilders group. “They’re afraid that, in a recessionary environment, they won’t be able to sell them.”

In June, 824,000 single-family homes were under construction in the US, more than at any time since October 2006, according to an NAHB analysis of government data. Unsold inventory has ballooned in part because of supply-chain disruptions and labor constraints that created bottlenecks in the production pipeline.

Now, with the economy looking murky over coming months, builders are cutting back on starts, trying to avoid having too many completed homes sitting empty. They’re also applying for fewer building permits, which for single-family homes fell in June to a two-year low, according to data from the government.

Not every market is cooling fast. But the change is stark in the pandemic boomtowns where builders piled in to meet demand for out-of-state arrivals, who often bid up prices beyond the reach of locals.

“It has become a very competitive market for builders where they are trying to offload any standing inventory,” said Ali Wolf, chief economist for Zonda, which tracks new-home production. “We may see a period where supply may actually exceed demand for a while in some of the markets that were the most feverish over the past two years.”

Boise, Idaho, is one of those areas where a pandemic bubble is bursting. Remote workers arrived from pricier states such as California, seeking open spaces and fewer virus restrictions. But now Covid restlessness is giving way to fears that the Federal Reserve’s cure for inflation — higher rates — will tip the US into a recession.

Idaho’s biggest builder, CBH Homes, has had about a third of buyers cancel contracts in the past few months, nearly twice the level at the start of the year, according to Corey Barton, the company’s president. He’s got 200 unsold finished homes, compared with 75 at the end of last year, and said he’ll probably surpass the 350 he was left with after the last crash 15 years ago.

In a sense the inventory was there all along — it was just hidden, he says.

Builders had been deliberately holding back houses, waiting until they were a couple months from completion before releasing them for sale. That’s because they couldn’t build fast enough to meet sky-high demand. By waiting, they could charge the current market price as materials costs climbed.

But now, the market is getting flooded with listings, Barton said. Homes are finishing or are getting listed earlier in the construction process.

Meanwhile, CBH has cut starts by about half. Subcontractors involved in the early stages of construction, digging out basements or pouring foundations are already feeling it, he said.

“The movement from out of state caused a false market,” Barton said. “We have to accept things for the way they are. It’s going to get tough.”

The builders most likely to get into trouble are smaller ones that need sales to pay back construction loans, or those who loaded up on land at today’s elevated prices, said Carl Reichardt, a homebuilding analyst for BTIG. Large public companies have cheap long-term debt and strong balance sheets, with more geographic diversity to balance out weak markets, he said.

Still, builders such as PulteGroup Inc. and D.R. Horton Inc. have warned investors of slowing orders and increased cancellations. The S&P Supercomposite Homebuilding Index has tumbled 27% this year through yesterday, more than double the 13% decline in the S&P 500.

Builders are reluctant to add too many homes to their pipeline when they don’t know where interest rates — and buyer demand — will be when homes are completed, Reichardt said. They also are contending with rising inventory in the existing-home market, giving house hunters other options, according to housing economist Ralph McLaughlin. The number of active home listings nationwide jumped 31% from a year earlier, a record increase, according to a report Tuesday by Realtor.com.

“Existing inventory was at historic lows so buyers turned to new homes to fill the gap,” said McLaughlin, chief economist for Haus, a co-investment platform for buyers. “If existing inventory now rises to normal levels, builders aren’t going to have the upper hand they had for years.”

Most traditional sellers can afford to wait or even postpone a sale if conditions deteriorate. But builders will have to discount until they find the market-clearing price, said Benjamin Keys, a real estate professor at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School.

He worries that at the end of a potential recession, continued underbuilding will help keep prices elevated.

“The homebuilders have an understandable incentive to pull back right now and Americans need more affordable housing,” Keys said.

At Saratoga Homes’s Glendale Lakes sales office, marketing director Christina Nuon said she’s making cold calls to agents and hosting happy hour events to boost sales. The company has a menu of incentives to bring down costs for its entry-level buyers, from $12,000 toward closing costs to a subsidized 30-year mortgage rate of just under 4%.

“Buying down rates, it’s kind of going to be our incentive probably from now on out,” Nuon said. “Just because that’s the only way we can help buyers. We can’t reduce the price any lower.”

Brown, the sales consultant, says the incentives have helped put a dent in inventory.

“I am trying to find one buyer at a time,” he said, “and not get overwhelmed by what I have coming up.”